In September 2011, a group of young Arab women, myself included, conspired to organize a DC Palestinian Film and Arts Festival (DC-PFAF). Inspired by the gigantic models established in Toronto, Chicago, London, Houston, Ann Arbor, and Boston, we decided to emulate this model in Washington, DC. We believed it would also provide an on-going artistic project for young Palestinian organizers, many of whom are active with the US Palestinian Community Network-DC (USPCN-DC).

The USPCN is a network of Palestinians in the North American diaspora committed to three national principles: self-determination and equality, the end to the occupation, and Palestinian refugees’ right of return within the meaning of UN Resolution 194. The network’s primary focus has been to resuscitate a self-empowered Palestinian national body that is able and committed to represent its own interests.

We proposed the idea of a film festival, motivated in part to avert the risk of atrophy among the local chapter during political lulls. DC-PFAF is now becoming a registered independent non-profit organization, and its organizers overlap significantly with USPCN-DC.

In its conception, we meant DC-PFAF to have the capacity to narrate. This led us to construct a project based on the identity of the filmmaker as opposed to the subject of the film. Conceivably, many Palestinian film festivals featured films about Palestine--about its hostile roads, the brutalities and deprivations of military occupation, the violence of forced exile, and the endemic insecurity of its subjects wherever they reside. The purpose of such festivals is to tell stories that are otherwise marginalized by political and national interests and, in doing so, to challenge those norms embodied in society`s mainstream ethos. Though we supported this motive, we also recognized the imperative of centering subjectivity. Palestinians have diverse identities beyond their political condition and affirming those is integral to the political project of resistance.

Nadia Daar, a DC-based Arab-Canadian, and a founding member of the DC-PFAF, explains her conviction about the importance of centering the festival on the filmmaker rather than the film’s content. She explains, "This Festival, instead of highlighting the story, shines the spotlight on the storyteller. Palestinians, whether they are living in occupied lands, in refugee camps in Lebanon or Jordan, or in Europe or North America, all have different stories to tell. But they share common histories, language, cultural elements, and potentially a common future. This is the common thread that links the artists together and shapes the stories they tell."

In our conversation, I recalled to Nadia my experience at Hany Abu Assad`s premiere of "Paradise Now" at the National Geographic Theater in Washington, DC in 2006. After the close of the Oscar-nominated film, the Palestinians in the audience were largely indignant. Frustrated that this opportunity to amplify their narrative may have been squandered by Abu Assad`s emphasis on the aesthetics of dignity, they asked why he did not show more tanks. He replied then that he sought to capture "the beauty" of Palestinian lives. Arguably, this was a beauty—a humanization—that made Palestinians more indistinguishable from all other persons. The audience would not have it: a film about Palestinians should be a film about Palestine.

This reaction reflects a popular social ideology that emphasizes displacement and dispossession as demonstrative of a persistent colonial condition. The desire to present and to see Palestinians (in their suffering) as exceptional often foregoes a discussion about an evolving community, globally dispersed, uniquely tied, and rife with the most extraordinary and the most banal events of life. We wondered whether it is necessary to ask not only where those Palestinians have been displaced from but also, where are they now? Is there value in evaluating the varied meanings of being Palestinian, even if it does not have a direct impact on, or pay explicit homage to, a liberation movement?

As a group, we endorsed the value of this endeavor and organized the first Festival in September 2011. Between our first organizing meeting and the launch of the Festival, we had expanded it to include Arts as well as film. The group agreed that highlighting subjectivity meant featuring performance and visual artists as well. We included social media personalities like Ahmed Shihab Eddine, formerly of Al Jazeera`s "The Stream," Yousef Erakat of "FouseyTube," as well as musicians, including Huda Asfour, one of the Festival`s founding and leading members, However, the Committee did not manage to include visual artists in its inaugural debut. Nadia explains that is why the organizers plan on hosting a visual arts exhibit at this year`s Festival. She said, "Artists tell stories through a variety of media and we really want to explore this idea through this Festival, so while there is indeed a strong emphasis on film, there will also be significant space for other forms of art."

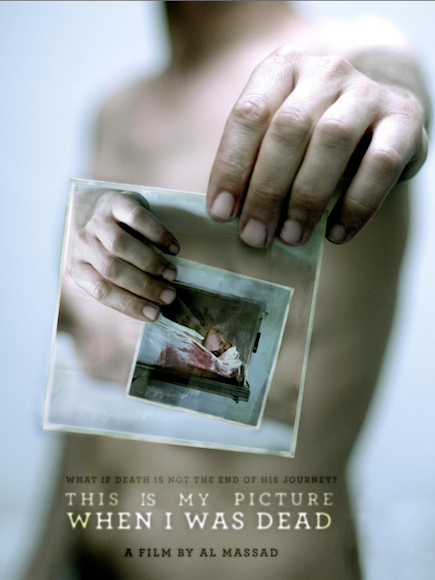

During the first Festival, our commitment to Palestinian agency and subjectivity drew criticism and praise alike. We opened the week-long series of events with Mahmoud Al Massad`s film, "This Is a Picture of Me When I Was Dead." The film featured the grown up son of an assassinated Palestinian leader. Bashir Mraish, who was four at the time, remembers his father`s assassination and pieces together his story as a twenty-nine-year-old man. Mraish is a cartoonist living in Jordan shown endearingly caring for his mother who yearns to see him marry. He is not particularly charming or admirable. The viewing audience is somewhat confused as they search for the Festival`s thematic motive. By the second day, and the second introduction, it is clear: we want to affirm the agency of Palestinian artists to narrate regardless of what they say.

[This Is My Picture When I Was Dead by Mahmoud Al Massad, 2010]

Nadia gushes that her favorite film of the 2011 Festival was Mahdi Fleifel`s "Arafat & I." Fleifel, who directed and starred in the film, portrays a hopelessly romantic young British Palestinian man navigating his love for Palestine embodied in former PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat while searching for young love in London. The film included a scene with partial nudity, which generated chagrin among the audience. "Some in the audience didn`t like the explicit nudity. It completely caught them off guard." Nadia explained that due to its progressive overtones, the film managed to challenge the Arabs in the audience as much as it did the ambivalent sympathizer with the Palestinian cause. She explained that this served a less explicit purpose of the Festival, “This is a project as much about disrupting misconceptions about Palestine and Palestinians as it is about pushing our own social boundaries as Palestinian and Arab communities. We are proud to be pushing the boundaries with this Festival."

[Arafat and I by Mahdi Fleifel, 2008]

Perhaps this social agenda reflected the composition of the organizers whose core included half a dozen woman and two men. Familiar with the enduring tension between national and gender liberation in our varied experiences as political and grassroots activists, we sought to reconcile it in practice and without fanfare. Due to the exceptional number of women filmmakers in our Festival`s collection, we dedicated a night to featuring their work. In 2011, we highlighted the films of Dana Abourahme and Mahasen Nasser-Eldin, who each, in turn, highlighted women subjects. Abourahme`s "Kingdom of Women: Ein el Hilweh," tells the story of seven women who enabled their families to survive in the aftermath of Israel`s 1982 invasion of Lebanon that destroyed the camp and led to the imprisonment of their male counterparts. Nasser-Eldin`s two short films each focused on a single Palestinian woman. While "From Palestine with Love" documented the tale of a young dancer eager to begin her life with her Swedish boyfriend in Stockholm, her film "Samia" celebrates the life of a 71-year old woman who has ceaselessly fought, and continues to fight, for her community`s right to education and residency in Jerusalem.

We also featured May Odeh`s "Diaries" on a separate night. Odeh is a Palestinian young woman who travels to Gaza and finds herself sealed in by its arbitrary siege. Though she only intended to stay a few short weeks, her inability to leave forces Odeh to remain in Gaza for nearly three months. She documents her stay as a subject while also following the intricate lives of three young women. Odeh manages to delicately portray a struggle against a double-siege, one imposed by the Israeli military occupation, and the other imposed by a conservative society and a quasi-religious political authority. To celebrate resilience, which draped Odeh`s "Diaries," we ended the evening`s program with spoken word, testimony, music, and poetry from locally and internationally-based women artists and activists.

[Diaries by May Odeh, 2011]

The Festival also featured one of Palestine`s most prominent filmmaking storytellers, Elia Suleiman. Suleiman embodies the theme of our festival as a Palestinian artist who tells the story of a nation by talking about himself. "The Time that Remains" is the third installment of his loose trilogy that examines his life, along with his family, as dispossessed Palestinians who never left their homes and became the second-class citizens of a Jewish Israeli state. The film includes little dialogue and is as poignant for its story as it is for its breathtaking images recreated by the film`s artistic director, renowned artist, Sharif Waked. "The Time that Remains," which earned substantial acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival, also attracted DC`s artistic community, who, though perhaps uninterested in Palestinians or Palestine, were drawn to its auditory, visual, and narrative prowess.

[The Time That Remains by Elia Suleiman, 2009]

The complete 2011 Festival spanned five days and nights, held at four different locations, featured four feature length films, eight short films, poetry, live music, and comedy. In the process, it also cultivated a dedicated group of young organizers eager to share this message of agency, empowerment, and diversity. In that spirit, this year`s Festival will also feature a category of amateur youth-made films to showcase the work of up and coming artists. Nadia adds, "There are few spaces dedicated to featuring the work of youth filmmakers, let alone young Palestinian filmmakers." Indeed, even in its nascent stages, the DC Palestinian Film and Arts Festival is continuing to grow and to push the boundaries of engagement with the question of Palestine. The Second Festival will take place in the Fall 2012.

[This article originally appeared in Badil’s Arabic-language publication, Haq Al Awda]